The headline that's attracted all the attention is that Glenda Jackson is coming back to acting after 23 years as an MP to be our narrator, the 104-year-old Adelaide Fouque. She's also in scenes in episode 1. I can tell you, it was one of the most overwhelming experiences of my life sitting in a room watching Glenda Jackson speaking my lines. She carries in her voice undeniably commanding authority, moral integrity, a wealth of wisdom and experience. And she makes these astonishing choices, sometimes driving through the lines, sometimes gliding around them, finding doubt in certainty and always looking for complexity. And sometimes she alights on a word and she knows that it can take force and she pushes on it and all that experience, those 55 years of work turns the air into fire.

But it's not just the Glenda Jackson show; we've got together the most wonderful casts. Alongside Glenda Jackson in episode 1 are Robert Lindsay, Fenella Woolgar, Ian Hart, with Ashley Margolis and Shannon Flynn as the young lovers. At the beginning of each recording block you do a read-through; often actors, quite rightly, hold back, wanting to keep their ammunition dry for the actual recordings; this time, each raised their game, spurring each other on, outdoing each other, and the read through was one of the best I've ever attended. Listening in the cubicle as Robert Lindsay tries out different ways of saying a line to find the funniest version, Jesus: I wish I could meet the ten-year-old me watching and loving Citizen Smith or the twenty-year-old watching and loving GBH and tell him what was going to happen.

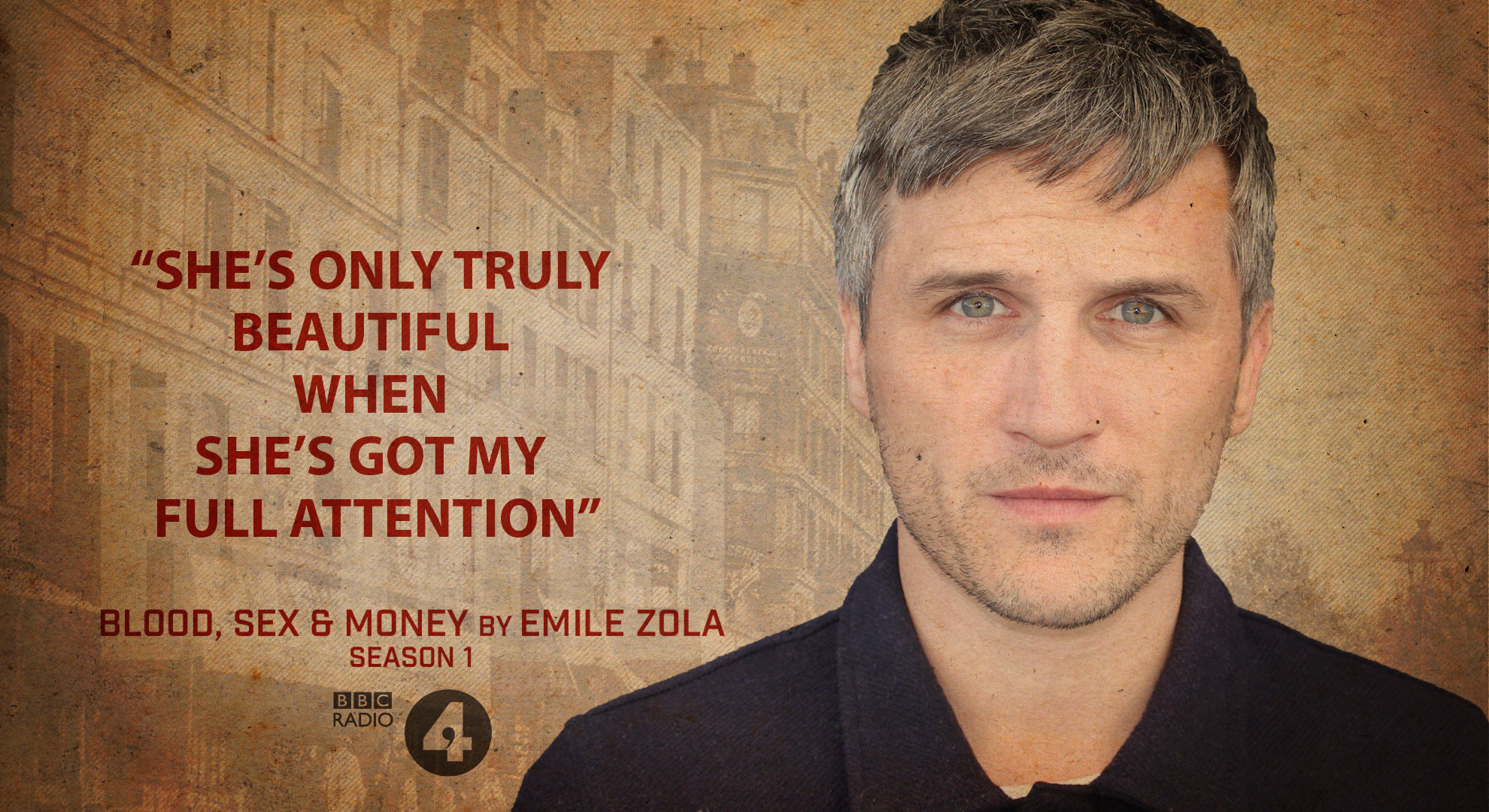

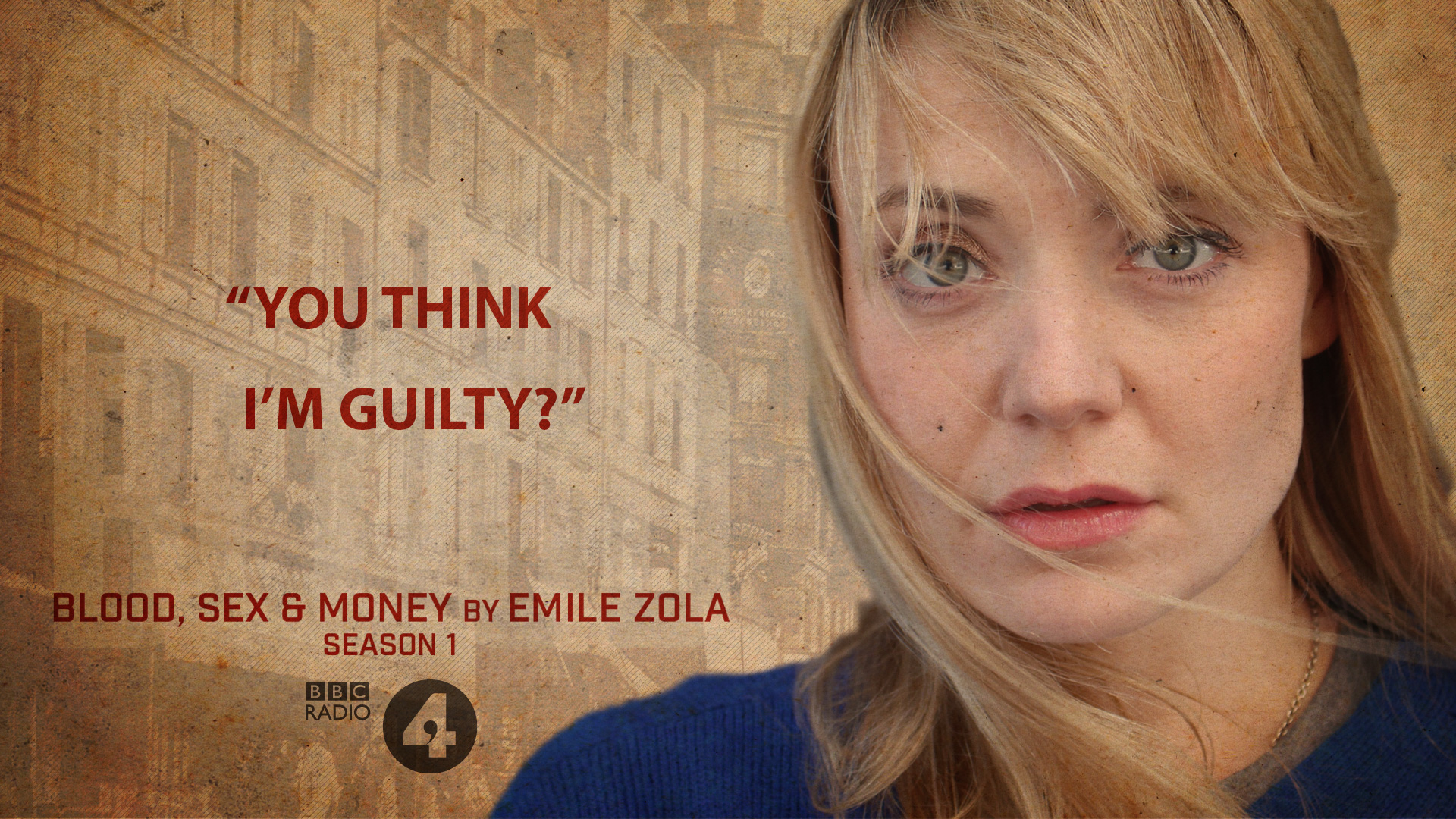

In episode two we have the wonderful Sam Troughton and Carla Henry, and also the lovely David Annen (with whom I've worked on three plays with very long titles: Here's What I Did With My Body One Day, And So Say All Of Us..., and My Life Is a Series of People Saying Goodbye). All beautiful actors. Sam Troughton full of warmth and feeling and exquisite comic assuredness, David Annen quiet authority, restless intelligence. In episode 9, we have the smashing Christine Bottomley, the wonderful Will Ash, and the lovely Sean Gallagher (who was also in My Life is a Series...). Will Ash all troubled intensity, Christine Bottomless seductive giggles and the most fantastic acting intuitions.

Elsewhere in the week there's Julie Hesmondhalgh, Bryan Dick, Robert Jack, and Georgina Campbell. It's a wonderful thing to be part of and I think it'll be pretty great.

The announcement got quite a lot of coverage, press and internet, local and international:

I'm not expecting you to follow those links. I just want to remember a time I wrote something that had to be embargoed by the BBC.

![photo[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513c543ce4b0abff73bc0a82/1362919072201-PZO854G4SEB794DVOEI8/photo%5B1%5D.jpg)