I’ve written comments on plays in this blog. I’m still feeling my way with this but I want to make a distinction between these comments and reviews. I’m not reviewing plays; I’m not a reviewer. The point of these are partly as an aide-memoire for me, partly a way of working through my thoughts about dramaturgy and playwriting. For that reason, the comments on shows I’ve seen comment almost exclusively on the play itself, and not much about the director, actors, designers etc. This of course makes them look like reviews because it’s a notorious failing of many British critics that they review pieces of theatre as if they were rehearsed readings of plays. In my case, I hope I am responding to plays as a peer and colleague, trying to get inside what the plays are doing and, if I have problems with the plays, then using them to think more sharply about what I am doing. (This does not inoculate me against criticism for my comments since, yes, I have chosen to make these dramaturgical notes public - because I think they might be interesting to other people - and I generally write about these plays soon after seeing them so they represent a pretty undigested response to the plays.)

I should also say that I know and like

very much some critics - Karen Fricker, Aleks Sierz, Andrew Haydon a bit

- and don’t mean any disrespect by distancing myself from their

profession, but I don’t like it when playwrights set themselves up as

critics. I’ve generally refused Night Waves and Saturday Review and Front Row for that reason.

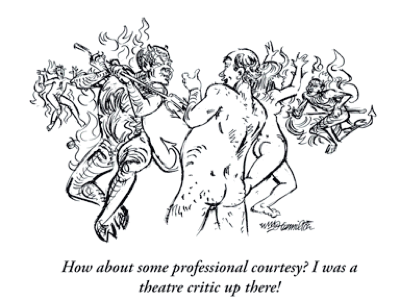

I'm also uncomfortable as a playwright writing reviews of other playwrights. This is a curious thing since the Saturday review pages are full of novelists writing reviews of other novelists; poets also don't hold back from reviewing poets. But you rarely see playwrights reviewing playwrights. The only major example was George Bernard Shaw and he moved from one to the other. Some critics have written plays - Jeremy KIngston, Nicholas de Jongh - but not with distinction. Is it something about the public nature of the play that makes breaking rank all the more disloyal? Or is theatre, despite all rumours to the contrary, a generally much more supportive and less bitchy place than literature?

![photo[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513c543ce4b0abff73bc0a82/1362919072201-PZO854G4SEB794DVOEI8/photo%5B1%5D.jpg)