23 July 2016. Welcome to the world, darling boy.

The Suspicious Death of Émile Zola

BBC Radio 4, 30 July 2016, 10.30am.

Radio 4 have a comedy-documentary series called Punt PI, in which Steve Punt (The Now Show, The Mary Whitehouse Experience) investigates historical mysteries. In this week's episode, he's asking if Émile Zola was murdered. The story is that in the early autumn of 1902, Zola and his wife went to bed with the fire on in their bedroom. In the small hours, both started to feel sick, though Zola was convinced it was nothing serious. In the morning, the servants had to force the door and found Alexandrine unconscious in the bed and Émile dead on the floor.

Most people have considered it a tragic accident, the result of a poorly cleaned chimney which fed carbon monoxide into the room. But Zola had many enemies, particularly as a result of his intervention in the Dreyfus Affair, and when in the early 1950s, Libération reported that a chimney sweep had made a deathbed confession to the murder of Émile Zola, speculation rose and his been high ever since.

Of course, it's probably impossible to know if he was murdered or not, though to my mind it's certainly not inconceivable.

I was interviewed down the line at the BBC's Paris studio - ironically, although Steve Punt visits Paris for much of the programme, he interviewed me in Paris while he was still in London. As is usual with these things, I cycled away from the recording feeling I'd said nothing of interest and sounded like an idiot, but the bits they used of me in the programme make me sound reasonably intelligent.

It's a fun, enjoyable programme and you can listen to it below:

(In case anyone's listening to this because they're writing an essay or something: near the beginning, he says that Zola's 20-volume Rougon Macquart novel series concerned the French Second Republic - in fact it was the Second Empire.)

UPDATE: Pleasingly, the programme - and my segment of it - was featured on Pick of the Week on Sunday 31 July 2016. You can listen to that HERE for a month.

Precarious Naturalism

I gave a paper at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama yesterday. Kim Solga is a visiting fellow there and she has a longstanding interest in naturalism, particularly a very interesting project of engaging with but complicating the political critiques of naturalism as a contemporary practice. She's also very interested, as am I, in Katie Mitchell's work which we both see as a contemporary avant-garde naturalist theatre practice. We discussed and decided to make her research seminar there a double-header, with Kim giving a talk and I giving a response.

The particular issues that Kim was interested in are work and labour, and the precariousness (or precarity as people are currently saying) of that labour. She also drew my attention to Jonathan Crary's terrific recent book, 24/7, which takes as its starting point capitalism's constant encroachments on sleep as a kind of last bastion of corporeal resistance to the round-the-clock creation of profit.

Under the joint title 'Precarious Naturalism', our papers were interestingly complementary. Kim gave a rich and nuanced paper looking at moments in Katie Mitchell's work that disrupt time, which resist the accelerating onrushing conversion of time into nothing more than an opportunity for consumption.

My paper looks at the contradictory and paradoxical relationship between Naturalism and precarity. On one hand, Naturalism pays close attention to ordinary people; not tragic heroes, not exceptional or high-born people but ordinary people with their flaws and weaknesses; we are given opportunities to pay attention to them, to feel concdern for them, to feel the weight of that individual life. In addition, Naturalism tries to bring out the individual human heing with real vigour, stripped of the generalisations of classicism or romanticism and the codified gestural languages of melodrama, revealed in its actual particularity. On the othe, it breaks down the boundary between human and animal (the Naturalist human is 'just' and 'no better than' an animal) and between humans and machines (human beings are predictable, their operations finite, their behaviour in principle reducible to a number of organic algorithms). They are also half-living half-dead, constituted by social and biological forces and principles that are not themselves alive.

I find a similar ambivalence in Katie Mitchell's work which both uses technology as a means of scrutinizing the ordinary and everyday but also offers a vision of the human being reduced and marginalisaed by the machine.

I then considered some debates about the status of looking and images. Jonathan Crary's much earlier book Techniques of the Observer suggested that the early nineteenth century saw a dramatic shift in the meaning and experience of looking. Images now became a kind of monetized economy; images began to circulate, stripped of their referents, distributed and exchanged across the world. Photography was a symptom, not a cause of that. I ask if Naturalism might be simply part of that. I conclude not, but think there is some ambivalence there.

Ultimately, I suggest, it's the comtradictions in Naturalism that are the source of what makes it a valuable political resource. It doesn't seamlessly duplicate the world but subjects it to contradictory scrutiny (fact and value, description and prescription) that interrupts the continuing encroachment of capitalism on time and the endless conversion of experience into commodity images.

Flagging

The Royal Court wanted some instant responses to the EU Referendum result for a Tumblr and so I wrote this. It was, quite honestly, a bit of automatic writing, pretty much, and took about 20 minutes, but I was - and still am - in a state of horror at the total disregard for honesty, evidence and argument in this whole debate and I wanted to express something about that,

I love my flag.

I love the flag.

This flag is about us, and me, no, us.

It’s called Union because it’s a tribute to the Union of Carlisle who were the, well, mercenaries who assisted in the Pennant War that led, bit by bit, to the formation of the United Kingdom.

It’s called Jack after Jack Friday, the leader of the Ranger Riders who galloped from town to town in the 1460s taking foodstuffs from the tables of rich lords and distributing it to the poor, which I read about on a website, because I think you have to, because there’s a tradition in this Isle of ours and we must never forget it.

I’m no expert but it’s what I feel.

It is blue because the first flag makers wanted to remember the dark of a night sky, those skies when they would sit in their broad yards sewing the first flags, looking up at the sky and blessing their freedom, the freedom that had to be in the flag, of course it had to be, so they took crocus petals and they crushed them in alcohol and left them for six nights and then used the unctuous liquor to stain their flags, deep and dark and free.

And then it’s red, red as blood, the blood spilled in the War of Ice Paper, so called because the cruel and rebellious Scots captain Abhainn mac Cennédig who took a treaty offered by the British at the beginning of the year 1681 and threw it into the loch where it froze so solid men could ride horses across it and legend has it this man in a pub told me that in the battle so many died and so much blood was spilled that the loch froze bright red, red as this flag I am holding against my thighs now, and so it had to be in the flag, it had to be.

There are crosses on the flag.

I am so happy there are crosses.

I heard that the two crosses are the true cross, the first of them the cross of Joseph of Japha, the man who carried his cross on his back for eighty years, some say ninety, walking across modern Syria spreading the Word of Jesus to all who would listen, and some who would not, and this diagonal cross reflects his crooked legs and yet never stooped and always spoke truly.

His message was heard by the Crusaders.

Some say he’s still walking, I don’t know about that but I know what I know.

The second cross is a sign that says no entry, this land is not for you, because we are here, we who traced our Saxon feet along the cliffs, you know the story, it’s a famous story, I don’t need to fill it in, but the chalk falling as the leather sandal scraped a line across the cliff edge? Yes, this is the chalk cross that says we are here and you will not pass, no passerán! as they used to say in Anglo-Saxon.

I heard these things and I love them and I know them because they feel right and when I hold this flag I know them even more.

Helen McCrory in Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea (National Theatre, 2016)

British Theatre in the 1950s

Helen McCrory in Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea (National Theatre, 2016)

I'm on a panel at the National Theatre next Friday. On a panel and not chairing it, for a change. We're considering British Theatre in the 1950s. This accompanies the National Theatre's new production of Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea which has recently opened to enormous acclaim.

Alongside me will be Michael Billington, veteran theatre critic of The Guardian of course, and also Julius Green, who has just published a pugnacious defence of Agatha Christie's theatre career, arguing that she is the most successful playwright of the 1950s. The panel will be chaired by Rachel Cooke, who wrote Her Brilliant Career: Ten Extraordinary Women of the Fifties which I thoroughly recommend for its fascinating rediscovery of ten remarkable women who lived eye-poppingly bold lives.

The event is on 1 July 2016 at 6.00 in the Lyttelton Theatre. Tickets can be booked on the National Theatre website.

What Happens When Nothing Happens?

I gave the opening keynote yesterday at the Sorbonne's L'Esthétiques de l'absence/Aesthetics of Absence conference, organised Bastien Goursaud, Elsa Lorphelin, and Déborah Prudhon with the support of the VALE research group. The title of the paper was 'What Happens When Nothing Happens: Thoughts in Theatre, History & Absence'.

The theme of the day was 'absence' and I decided to look at in terms of historical absence - specifically how to take account for absence in history, by which I mean Things Not Happening. It's an important question for me, I think, because of the Naturalism project. In particular, Naturalism seems to me such a monumental and obvious idea in theatre, it can sometimes seem hard to imagine that it wasn't inevitable - or that it inevitably turned out the way it did. I have been trying to think about its contingency (that it was the product of decisions and encounters which might have been otherwise) and its specificity (that its forms and practices derived from and had specific significance in relation to its original context in a way less apparent to us now).

Both of these ideas - contingency and specificity - might seem to tend towards historical counterfactualism. If Naturalism was contingent, it seems to follow that it could have been different. And if it was historically specific, it seems to follow that if the historical context were different it too would have been different.

But, I argued in the paper, we should proceed with caution. Counterfactual history is philosophically and politically dubious. Philosophically, because it drives a coach-and-horses through the eternally intractable debate about free will and determinism. In a strictly determinist universe, counterfactuals are impossible because the way things are is the only way things can be. They seem to assume either indeterminacy (and some counterfactualists like to mention some findings in quantum science that proves it is possible) or free will as something that is uniquely self-causing. The problem here is that indeterminacy doesn't get you what you want - counterfactuals are stripped of their interest if historical causation is random; the counterfactualists typically want to believe that better decisions could have been made with predictable and better consequences. And free will is also not maybe the panacea the counterfactualists want because what is a free will? Is it completely free of prior causation? If so, it would start to seem like random indeterminacy. In fact, surely, the only free will worth having is the freedom to act on good reasons (rational self control). So I do x not just on complete arbitrary whim but because I have judged that x is the best thing to do given my knowledge and understanding, my projects, attitudes, aims, and so on. But hold on, because that starts to look like determinism: given my knowledge and understanding, my projects, attitudes, and aims (let's call all of that y), I could only have done x - to the point where it seems hard to distinguish between saying (a) I did x because of y and (b) y caused x. Once you get to the latter, the free will seems to be kicked off the pitch and once again counterfactuals are impossible.

(There is always compatibilism; the idea that you can have your determinist cake and freely eat it too, but I tend to agree with Kant that this is a 'wretched subterfuge' comprising mostly sophistry.)

Politically, there is an additional, though less important, concern, which is that most British counterfactual history enthusiasts over the last thirty years have tended to be right-wing ideologues: Niall Ferguson, Andrew Roberts, Jeremy Black and so on. They make this ideological commitment very clear in their awful books which fulminate against the influence of Marxist in history (they construe Marx to be a very very strict determinist, which is a selective reading, to say the least). They nail counterfactualism's colours to the conservative mast because they say at its heart is, as Jeremy Black puts it, 'individualism and free will' (Other Pasts, Different Presents, Alternative Futures, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2015, p. 9). However, as we've seen, it's not at all clear that free will does give you counterfactual history, unless you posit human beings as purely arbitrary and capricious beings, entirely divorced from history, which is a pretty absurd fantasy, even for neoliberal cheerleaders like Niall Ferguson.

So, the paper talks about the problems of setting out the kind of contingency and strong historical readings that I want to do and ends by trying to talk about one particular absence: a handling of homosexuality in Naturalist theatre (a topic I've talked about before). I try to show that there are ways of talking about absence which does not rely on counterfactuals but also doesn't secretly turn in into presence (as a deconstructive queer reading might do).

There was a good conversation afterwards. One issue that came up genuinely puzzled me: what the difference is between counterfactual fiction and counterfactual history. The puzzle, for me, is that I have no problem with counterfactual fiction but I find counterfactual history rather suspect - and yet I'm not sure what the deep down distinction is. I am a bit of an Aristotelian in thinking that one can genuinely learn important things from art and literature, so it's not the 'cognitive' value of the two. I don't think I believe that history writing is pure impersonal fact and fiction writing pure personal imagination; the line is certainly blurred. I did like, however, the questioner's suggestion that counterfactual history is kind of like historiographical fan fiction...

Anyway, I was very honoured to be asked to speak at this event and pleased with how it went down.

Joseph Fiennes publicity shot for Ross by Terence Rattigan (Chichester Festival Theater, 2016)

Ross

Joseph Fiennes publicity shot for Ross by Terence Rattigan (Chichester Festival Theater, 2016)

Chichester Festival Theatre are reviving Terence Rattigan's little-known 1960 play Ross. The play is an historical epic about T. E. Lawrence's role in the Arab Revolt of 1916 - and the production is being launched to mark the 100th anniversary of that event.

I've been asked to do a couple of things around it. First I was asked to do a programme note for the production. I've contributed 'Rattigan Inside Out'. It's often thought that Ross is a complete anomaly in Rattigan's oeuvre, being an epic war play in which bandits and terrorists and soldiersdebate British foreign policy in the Middle East - not the domestic tales of thwarted emotion for which Rattigan is perhaps better known. But I try to suggest int the article that Rattigan's domestic plays have a broader, outward-looking social dimension - and that this play in fact is powered by Rattigan's empathetic account of T. E. Lawrence's private sexual pain.

And then the wonderful Nick Hern Books are releasing an edition of the play and, as usual, they've asked me to contribute a new introduction. This involved a lot of research, into the history of Arab nationalism, the contested and controversial history of Lawrence, Rattigan's writing of the play, his battles with the Lawrence estate, and the history of the first production and revival. I've tried to make a caes for the play as something more experimental than has been generally acknowledged and a play that may only now be able to find its audience.

Whether it will find an audience remains to be seen. Fingers crossed. The production stars Joseph Fiennes and Michael Feast and is directed by Adrian Noble.

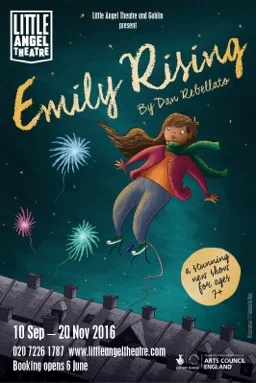

Emily Rises Again

My 2001 radio play Emily Rising is being reborn as a puppet theatre show for children. It opens at the Little Angel Theatre, Islington on 10 September and runs until 20 November.

Oliver Hymans is directing, and the rest of the creative team is Alison Alexander (Puppets), Jimmy Grimes (Puppet Mechanics), Rachael Campion (Set), and Patrick Furness (Sound). It's a co-production between Little Angel and Goblin Theatre, artistic director, Matt Bugatti.

We're workshopping the text and I'm reworking it, clarifying and reshaping it for the stage and for puppets, which is going to be a fascinating adventure.

Booking opens for schools and members on 31 May and to the public on 6 June. Book HERE.

Threepenny Opera (National Theatre, 2016). Photo: Tristram Kenton

See 3PO

Threepenny Opera (National Theatre, 2016). Photo: Tristram Kenton

The new production of Threepenny Opera by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, adapted by Simon Stephens, directed by Rufus Norris, has opened at the National Theatre to mostly very good reviews.

I was asked - rather at the last minute (maybe someone else fell through) - to write a programme note about Brecht. It came at a good time because in the last few years, Methuen (his publisher in Britain) have brilliantly revamped and expanded his works in translation with a hugely extensive reworking of the seminal collection Brecht on Theatre, but also new collections Brecht on Performance, Brecht on Art and Politics and a reissue of Brecht on Film and Radio. There's also been a translation of his novel The Business Affairs of Mr Julius Caesar and - just about to appear in an eye-wateringly expensive hardback - his Me-Ti: The Book of Interventions in the Flow of Things. The journals and short stories were reissued too. So I'd been relishing the chance to look at Brecht anew and had been devouring the new books.

I was asked to write a piece about Brecht how the theory developed, what his theatre was about and so on. I had a couple of goes writing something quite serious. But then it seemed to me that wasn't the tone of his own work - not the theatre, not the plays, not the theory - and I decided to do something much looser and a bit more pugnacious. So the piece is called 'Ten Cheers for Bertolt Brecht' and it offers ten reasons to love Brecht, his theatre and his politics, under headings like fun, theory, emotion, smoking, music, and learning. And I don't mention the word 'alienation' once.

And you can read it HERE.

Seven Jewish Children

In 2009, Caryl Churchill wrote a short play to raise awareness of the Israeli Defence Force's attack on Gaza (Operation Cast Lead) and to raise money for the British charity Medical Aid for Palestinians. The piece takes the form of a series of seven short scenes, taking snapshots of seven moments in the contemporary experience of the Jews and of the state of Israel; in each scene adults discuss how to explain to a young girl what is happening. Most of the dialogue takes the form 'Tell her...' This deferred and mediated structure is somewhat riddling and complex, the events being refracted through the child and the parents and relatives' various attitudes. However, almost immediately, Churchill was accused in some quarters of having written an anti-semitic play and even of having revived the medieval Blood Libel.

I gave a paper - Theatrical Images & the Theatrical Imagination: the scandal of Seven Jewish Children - at the Sorbonne's VALE (Voix Anglophones: Literature et Esthétique) research group. My basic claim is that the play is itself trying to speak about what it is possible and not possible to speak about. I suggested - rather clumsily - that the play is trying to hold open a space for complexity and ambiguity. By ambiguity, I don't mean it is trying to be even-handed or to sit on the fence: it is fairly clearly trying to understand why the Israeli Jews, having been on the receiving end of such suffering, are now able to mete out fairly brutal suffering on the Palestinians. (And let me say quickly, nothing in the play tries to suggest that there is any sort of equivalence between the Holocaust and the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians, which would be a crass thought.) What the affair reveals, I think, is that those who wish to close down cultural debate often resort to a kind of literalism about culture that closes down the imaginative spaces that art is particularly adept at opening. Art's ability to be metaphorical, ambiguous, to offer what Kant calls 'aesthetic ideas', that is, representations, references, concepts corresponding to the world but which have a kind of movement in them, a shimmer that allows them to slip their moorings and function in different ways, making lateral associations and new connections.

The talk provoked some interesting debate. Some doubted that the play is significantly ambiguous at all and that in fact it offers a fairly clear, polemical line against Israel (though no one in the room took seriously the suggestion that it is anti-semitic). It was suggested that the play's meanings are limited not by the rhetorical devices of its detractors but by our shared knowledge of Israel's history. When one of the parents says 'Don't tell they're Bedouin', I suggested the line could be understood as both a sincere and an insincere statement - and certainly could be played either way. The counter-argument is that there are historical facts to be considered: the indigenous Palestinian Arabs weren't Bedouin and that must arrest the ambiguous movement of the play.

As I was working on the paper, I found the play more and more elusive, which slightly hamstrung the presentation, but it was interesting to give some very provisional thoughts an airing and to have to defend them from some enjoyably robust questioning.

I'm Looking Through You

I gave a paper at the Alternative Victorians and Their Predecessors: New Directions in Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Performance Research conference at Warwick University, co-organised by Nineteenth-Century Theatre and Film & University of Warwick.

It's part of the Naturalism project. I'm trying to think through what the 4th wall idea might have meant in its specific historical context. To that end the paper tries to argue for the historical specificity of the 4th wall (distinguishing it in the 1880s from certain potential precedents for it). I then try to make the invisible wall visible, by trying to say what the 4th wall would actually have looked like if we could see it. In the process that reveals some interesting things about the nature of Second Empire architecture, the separation of private and public space and of private and public morality. And finally I then try to think through what its invisibility might have meant in context and that takes me further into Haussmanization and the Commune.

I think it's an interesting piece and I hope to develop it further for TaPRA this year. Baby permitting.

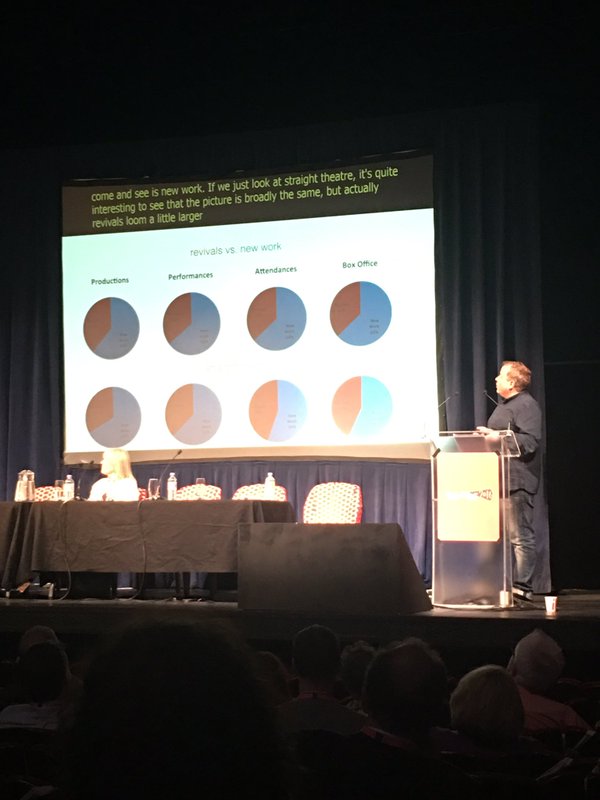

Theatre 2016

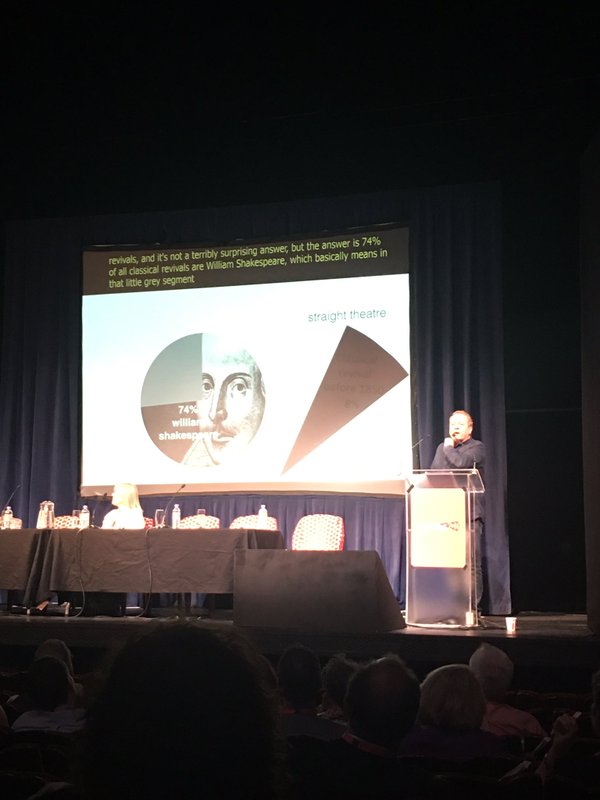

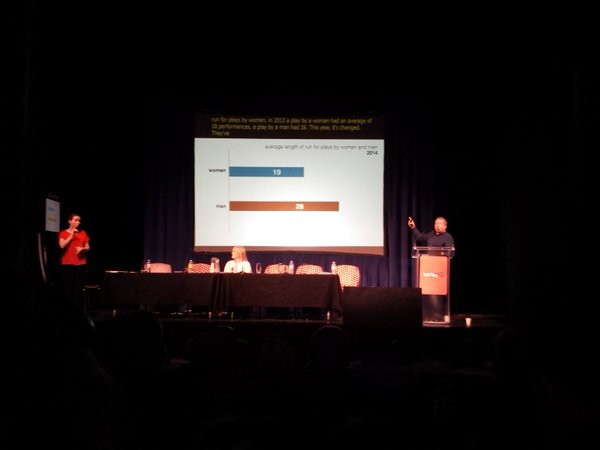

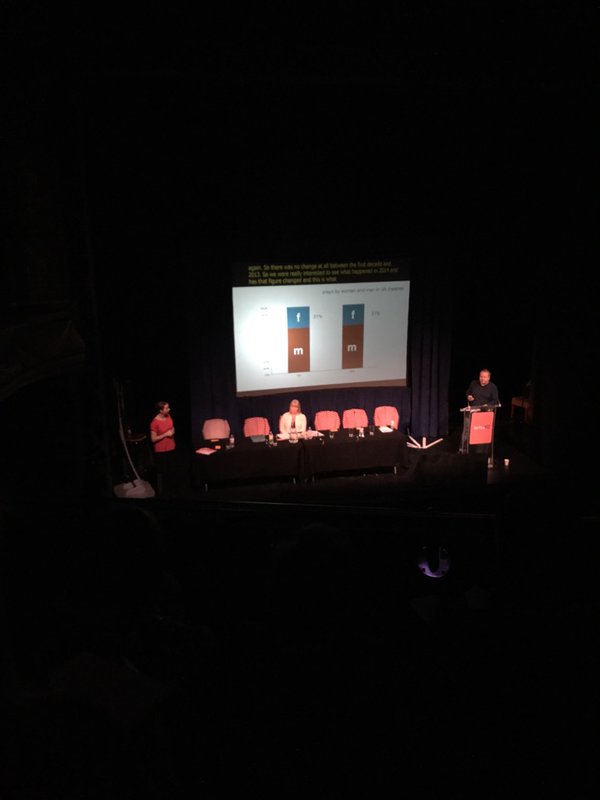

Theatre 2016 is the biggest UK theatre conference ever, apparently. Organised by BON Culture and its partner organisations, it ran at the Piccadilly, Lyric and Arts Theatres in London over 12-13 May 2016. It had something like 1000 delegates. I was asked by the excellent David Brownlee (cofounder of BON Culture) to give the opening keynote, presenting our British Theatre Repertoire 2014 report (of which David was a co-researcher), but also a report by BON & partners on the 'Hopes and Fears' of the theatre sector for the state of the industry now and over the next decade. I was pleased with how it went, given that I was a bit sceptical that what the theatre industry wanted to kick off their conference was a lot of pie charts, but they liked the jokes and actually gasped at some of the facts. That's particularly satisfying, given that I think this data is rather remarkable but it can be quite tricky to get people excited about facts and percentages. In addition, I think we made some excellent connections with some other industry bodies to build this dataset and make it something even more comprehensive a picture of what happens on British stages.

Mr Burns by Anne Washburn (Almeida, 2014) photo: Manuel Harlan.

British Theatre Repertoire 2014

Mr Burns by Anne Washburn (Almeida, 2014) photo: Manuel Harlan.

Last year, David Edgar and I (for the British Theatre Consortium) produced a much-cited report, British Theatre Repertoire 2013, gathering together and analysing the most extensive set of data ever assembled about what happens on Britain's stages. Well, we've done it again, producing a comparable report on the British Theatre Repertoire in 2014. Again we've been supported by Arts Council England and the report was researched and written in collaboration with UK Theatre/Society of London Theatre and with David Brownlee of BON Culture. Its findings were launched at a plenary session of the Theatre 2016 Conference, on 12 May 2016.

The main headline of the report is that the transformation ofBritish theatre repertoire which reported last year has remained firmly in place. New work still dominates the repertoire, and London the theatrical landscape. British theatre continues to defy austerity: in 2014, British theatres made over a billion at the box office.

This is the second report so while we can begin to establish the consistent patterns, it is too early confidently to describe trends (with only two years of data, it's not possible to tell whether a change is a genuine trend, random statistical variation, or the product of one anomalous year). We hope the funding will be continued. With another couple of years of data, we should be able to see a dynamic picture of where the theatre is going.

However, some changes can be seen.

- Within new work, new writing has slightly declined and devised work markedly increased. In terms of attendances and box office, London has pulled further away from the rest of the country.

- Wales seems to be experiencing a surge in theatregoing leading the country in percentage of potential attendance and box office.

- Classical revivals are dominated by Shakespeare and women’s revivals by Agatha Christie.

- More than half of the National Theatre's and RSC's new plays were by women.

The full report is embargoed until Thursday May 12 - at which point you'll be able to read it HERE.

Sarah Kane article # 2

On the heels of Sarah Hemmings' article, there's a good piece by Andrew Dickson in The Guardian today looking back at the premiere of Sarah Kane's 4.48 Psychosis (on the eve of an operatic version of the play).

I'm not specifically mentioned in the piece which I am absolutely fine about. I had a phone conversation with Andy to help with the research for it and he begins the piece talking about the day I got Sarah over to Royal Holloway - about which there is much else on this website.

What I like in this piece is the sense that the dust is settling a bit on Sarah's reputation. We're not so bowled over by the intensity and the violence and the shadow of her suicide has shortened. We can even note that, while this does not exhaust the play by any means, 4.48 Psychosis is in part a suicide note of an unusually rich and complicated kind. I also love the comment by Sarah's brother, Simon, that 'Mental illness is so often sentimentalised, or portrayed as madness – I hate that word. Sarah wanted to convey that while it may be pathological, it isn’t necessarily illogical' which seems to me exactly right about the play..

Zola Award

The BBC has an internal radio award ceremony, the Radio Awards. I was nominated once before but didn't win, to the Corporation's unending shame.

But Animals - episode 1 of series of of Émile Zola: Blood, Sex, & Money - was nominated and tonight it won.

I couldn't make the ceremony, being in Paris, so I haven't seen the award itself though it seems to be made out of a slate from the original roof of Broadcasting House, which is, goodness me, what a thing. And what a day, having my 4th Zola episode go out live this afternoon and having the first one win in the evening.

It's a prize for Best Drama Production (or reading), which means that the award is absolutely shared with Pauline Harris (producer) and Steve Brooke (sound designer) and, of course, an extraordinary cast that included Glenda Jackson, Robert Lindsay, Ian Hart, Fenella Woolgar and many more.

The judges citation reads: 'The judges said this was a gripping, entertaining piece of drama which conveyed the turbulent times of the Second Empire through the personal lives of its players. It was wonderfully well paced and varied, setting the tragic alongside the comic, interweaving the heroic with the grotesque and the pathetic.'

Routledge Drama Anthology

A few years ago (2010), I contributed to a big old textbook about Modern European and American drama published by Routledge under the title The Routledge Drama Anthology and Sourcebook: From Modernism to Contemporary Performance. I handled the section on Naturalism and Symbolism, offering a long introduction and overview to these movements and also translating Maeterlinck's Interior and 'Tragedy in Everyday Life' and Pierre Quillard's 'On the Complete Pointlessness of Accurate Staging' . Well it's gone into a second edition. My section hasn't changed but much of the rest has. And it's got a slightly snappier title. If you want a one-volume guide to some of the most exciting movements in experimental western theatre, you can't do better.

Gale, Maggie B., John Deeney, Dan Rebellato, and Carl Lavery. The Routledge Drama Anthology: From Modernism to Contemporary Performance. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

Royal Holloway and the Performing Arts

The QS World University Rankings produce annual league tables of university institutions broken down by subject. They are measuring reputation and impact and they ask the opinions of other academics and employers and gather data about the impact of research based on citations and other measurements.

Very pleasingly, my institution, Royal Holloway, has been voted 14th in the world for Performing Arts and 6th in Britain.

- Royal College of Music

- University of Oxford

- Royal Academy of Music

- Royal Conservatoire of Scotland

- Guildhall School of Music and Drama

- Royal Holloway, University of London

- University of Cambridge

- King's College London

- University of Southampton

- University of York

The rankings reflect the strength of Drama and Music at Royal Holloway but you'll note that all of the institutions above us on the list are either conservatoires or academic institutions that don't teach Drama (Oxford), so of institutions that teach an academic degree in Drama, we're first. (Not that it really works like that.)

This is particularly pleasing because we've done a lot of work focusing our research activity, rebuilding the research staff, raising the profile of the research and creative practice, and reshaping the undergraduate and postgraduate curricula. This already had a strong impact on our REF score last time and this is further evidence of our growing reputation.

Local Hero

Rebellato, Dan. "Local Hero: The Places of David Greig." Contemporary Theatre Review 26, no. 1 (January 2016): 9-18.

I gave a paper at Lincoln for a symposium on the work of David Greig a couple of years ago and a revised version of the paper has now come out in Contemporary Theatre Review. You'll probably need institutional access (unless you have wisely chosen to take out a personal subscription). It's part of a special issue on Greig's work, which I thoroughly recommend.

The first fifty of you can download the article HERE.

Sarah Kane article

There's a nice profile of Sarah Kane by Sarah Hemming in the Financial Times today, with some great contributions by Katie Mitchell, Vicky Featherstone, Alistair McDowall and others. It coinciding with Sarah Kane's premiere at the National Theatre with Katie Mitchell's production of Cleansed. I've written a programme note for that which I'll stick on here in due course.

But for now, here's the article:

Home Economics

I've written a short play for Radio 4 and it's on this evening, Saturday 6 February 2016, at 7pm. It's in the From Fact to Fiction slot, which is intended for short, punchy plays that address topical issues. Mine looks at austerity economics. It's directed by the brilliant Polly Thomas and has a tremendous cast of Frances Grey and Sion Pritchard.

Link here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06zh291

It's repeated tomorrow at 5.40pm and it'll be in the iPlayer for a month after that.

![photo[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513c543ce4b0abff73bc0a82/1362919072201-PZO854G4SEB794DVOEI8/photo%5B1%5D.jpg)