David Eldridge has just completed a trilogy of plays, Beginning (2017), Middle (2022), and End (2025). Each of the plays is a two-hander that unfolds in real time and each one concerns two people negotiating a key moment in a relationship. Beginning shows us a romantic relationship beginning; in Middle, a marriage faces a crisis; in End, a couple face not the end of a relationship as such, but the end of life itself.

David Eldridge is an anomaly. He is, without doubt, one of the great playwrights of our age; from the first play of his that I saw, Serving It Up (Bush Theatre, 1996), through masterpieces like Under the Blue Sky (Royal Court, 2000), Incomplete and Random Acts of Kindness (Royal Court, 2005), The Knot of the Heart (2011), In Basildon (Royal Court, 2012), to the recent trilogy, he’s created intensities of emotion on stage like no one else. And yet, he is barely written about. By that I mean, he is barely written about by academics. There isn’t (yet) a substantial critical bibliography on his work in the way that there is for a contemporary like Martin Crimp.

Why is that? In part, I think, it’s because of that word ‘emotion’. His plays are very emotional and I suspect a lot of academics think that’s too murky or imprecise a thing to write about. I also think the emotional impact of his work obscures, for some, the broader things his work is about. It’s also the case that his work is often naturalistic. I say ‘often’ as an act of hesitation, because some of the plays are very much not naturalistic (Market Boy [2006], Incomplete and Random Acts, Holy Warriors [2014]), but also because naturalism might be the mode of his scenes, but to say the plays are naturalistic ignores the elegance of the formal architecture of something like Under the Blue Sky, with its triptych of interlocked scenes, or the episodic rise and fall of Knot of the Heart. But the naturalism at work in his plays is perhaps another reason why academics have shied away from tackling his work: partly because of a misplaced view among some theatre scholars that naturalism is a conservative or old-fashioned form but more likely because naturalism seems to leave nothing for the theatre scholar to do. There’s apparently nothing to explain: no formal obscurity whose effects and significance one can elucidate, no symbolic referents to tease out.

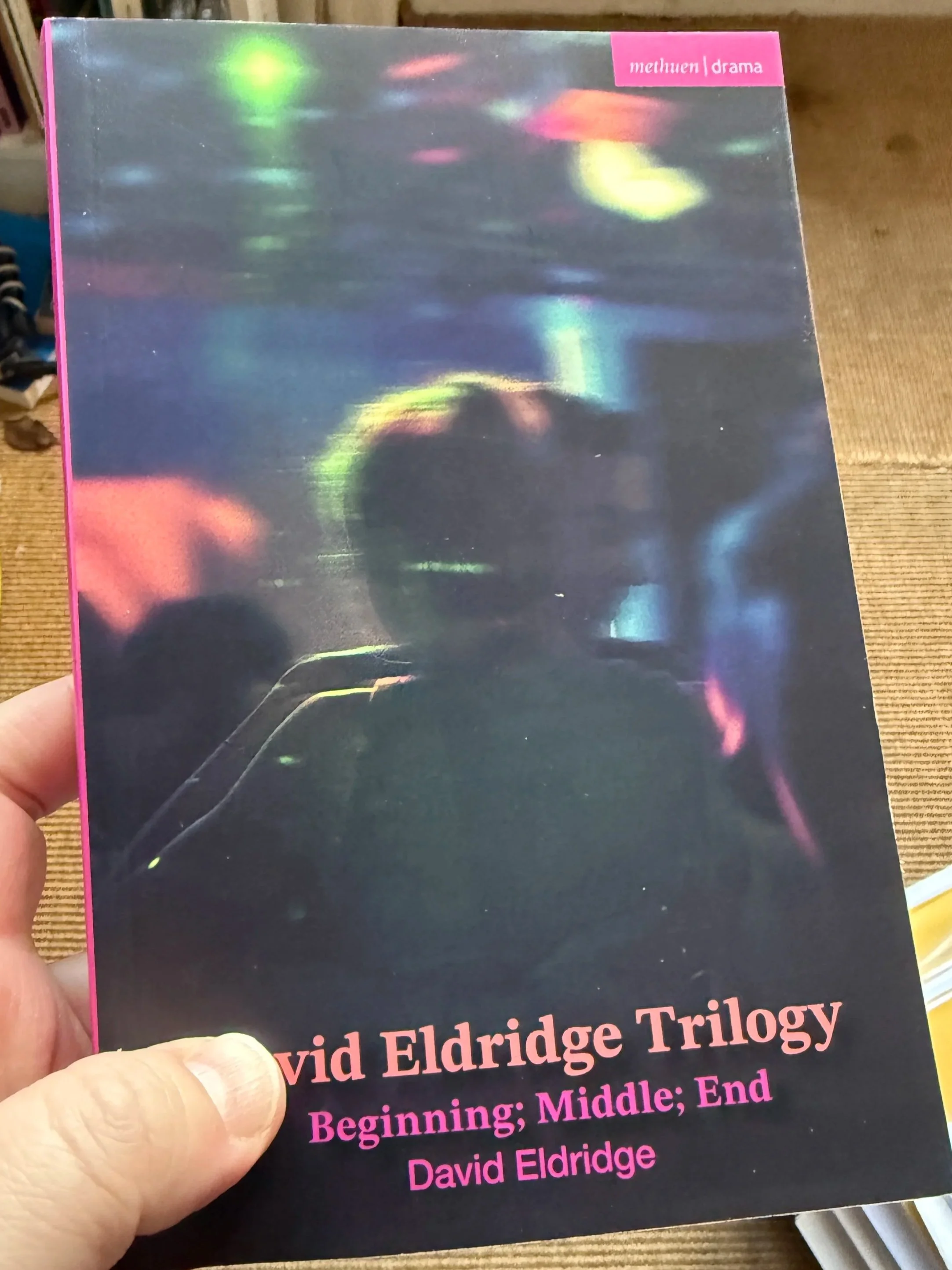

So when David approached me and asked if I would write something, I didn’t hesitate. As the third part of his trilogy headed for the stage, Faber had decided to publish all three plays in a single edition and he wondered if I might write an introduction. These are astonishing plays and it seemed to me important to underline their achievement, particularly because I suspect some people might see three domestic, relationship two-handers set in one space in real time as unambitious, safe, even, dear God, easy to write. So the piece I’ve written tries to elucidate the scale and ambition of these plays. In writing it, I think I’ve drawn equally on my academic and my playwriterly sides. The former tries to tease out the connections between them, the broader cultural landscape that they engage with; the latter tries to explain, for someone who maybe has never written a play like this and doesn’t know what it demands of the writer, just how remarkable the creative work is here.

And I’m pleased with the result. Available in all good bookshops.

![photo[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/513c543ce4b0abff73bc0a82/1362919072201-PZO854G4SEB794DVOEI8/photo%5B1%5D.jpg)